Winning by losing: Anwar Sadat had visionary strategy for 1973 Yom Kippur War

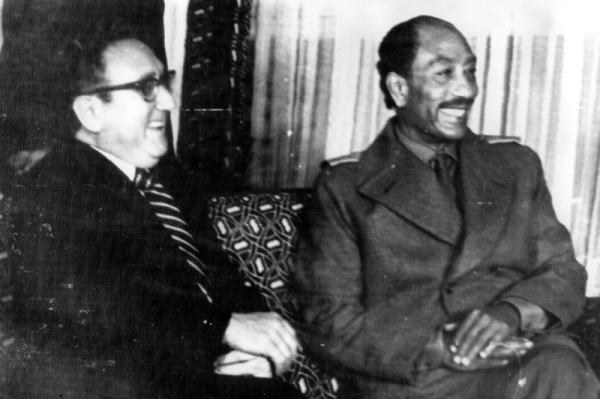

1 of 3 | U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (L) meets with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat at his summer retreat on December 13, 1973. UPI File Photo | License Photo

Friday marks the 50th anniversary of the fourth Arab-Israeli Middle-East war. Called the Yom Kippur War, as Egypt and Syria attacked on Judaism’s holiest day, and the Ramadan War, it occurred over that Muslim holiday in October 1973.

Egyptian and Syrian forces launched dual surprise attacks. Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal in the Sinai that Israel had captured in the June 1967 war. Syrian forces struck at the Golan heights in Israel’s north that had also been seized by Israel in the 1967 war. Advertisement

Initially, the combined Arab armies shocked the Israeli Defense Forces. Egypt’s army advanced well into the Sinai. The IDF’s piecemeal counterattacks took significant losses. In a few days, however, Israel recovered. Gen. Ariel Sharon recrossed the canal, trapping Egypt’s Third Army. Syria’s attack on the Golan was repelled and the IDF began advancing on Damascus. Advertisement

Two weeks later, a ceasefire was negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and the United Nations. In the interim, American and Soviet resupplies of both sides led to a crisis. U.S. President Richard Nixon raised America’s defense posture from the peacetime Condition 4 to Condition 3, a signal readily understood by Moscow. As the ceasefire took hold, the world settled back from what could have escalated into a superpower conflict.

While massive numbers of studies and analyses examined every aspect of that war, the most penetrating understanding was the one given to me by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat three years later in May 1976.

Then, America’s most senior military educational institution, the National War College, sent its students around the world on field trips to meet with key civilian and military leaders in Europe, Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Despite being the youngest and most junior faculty member, I was assigned to escort the 40 officer students sent to the Middle East.

Our last stop was Cairo. Our last meeting was with Sadat, who met with the group for about 50 minutes. The president’s staff had also scheduled another 30 minutes for me to meet privately with the president to discuss the 1973 war. Advertisement

The meeting did not last 30 minutes. It went on for so long that missing my flight to London was a real possibility. Sadat, sensing my discomfort said, “Do not worry. You will not miss your flight.”

Sadat described in great detail his aims and intentions for the war. Returning control of the Sinai was crucial. In 1972, Sadat declared that it was worth “1 million lives.” But how to achieve his goal against a far superior IDF? 1972 was crucial. Sensing the tectonic strategic shifts underway, Sadat would eject all Soviet forces, some 30,000, from Egypt.

By the end of 1972, with Nixon’s historic visit to China and the rapprochement that was occurring between Moscow and Washington over strategic nuclear issues, Sadat’s judgment proved correct. In secret discussions with Syrian President Hafez al-Assad, planning for the attack began. Realizing that surprise was essential, Sadat elaborated on how that was done.

Beginning in mid 1973, Egypt and Syria began a series of exercises and deceptions to force the Israelis to react. Prime Minister Golda Meir began a succession of mobilizations as deterrents to any attack. But these were costly. By October, Israel and its allies had been lulled into a false sense of security. No one expected an attack, especially on the afternoon of Oct. 6, 1973, Yom Kippur. Advertisement

Sadat knew that while his forces could cross the canal in Operation Badr and penetrate deeply into the Sinai, ultimately Israel would win a military victory. But it was the political victory Sadat had the vision to pursue. The IDF would prevail and force the Egyptian-Syrian armies to surrender. However, the stage was set ultimately for the peace that would occur between Cairo and Tel Aviv.

The assassinations of Sadat in 1981 and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 by ultra nationalists were among the greatest calamities of that era. Had both lived, the prospect for a lasting Middle East peace was at least possible. Still, Sadat’s strategic vision has sadly been lost over time — winning by losing.

About Pan American Flight 101 from Cairo to London, Sadat was correct. Kept waiting on the ground for about three hours for the last passenger to board — me — I made the flight. For those passengers wondering who this person was, I had the last seat in the last row next to the lavatory. Having contracted a bad tummy in Cairo, I needed it.

Harlan Ullman is UPI’s Arnaud de Borchgrave Distinguished Columnist, a senior adviser at Washington’s Atlantic Council, the prime author of “shock and awe” and author of “The Fifth Horseman and the New MAD: How Massive Attacks of Disruption Became the Looming Existential Danger to a Divided Nation and the World at Large.” Follow him @harlankullman. The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. Advertisement